There is a shift in spoken discourse, a flattening of the texture of human speech. It began in the quiet corners of the academy, but it has since spilled out into the noisy, unscripted sprawl of the internet. You hear it in the way a podcast host might, with suspicious fluidity, promise to “underscore a meticulous execution” or that they “delved into the opportunity to pinpoint rigor” or to “boast of a meticulous integration plan that will bolster adoption”. These are artifacts, little flags planted in our consciousness by an LLM.

A group of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development set out to find them. The influence of LLMs such as ChatGPT is already taken for granted in written discourse. Instead, the study takes a phonocentric approach, analyzing 740,249 hours of human speech. They analyzed 360,445 academic talks on YouTube and 771,591 conversational podcast episodes, searching for the moment when English broke. Following the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, they found a “measurable and abrupt increase” in specific words falling on a not-so-gentle upward curve.

Their results showed one shibboleth to be the most egregious offender, “delve”. Before Chat, we rarely “delved”. After the machine, we did so quite often. The word choices of the machine are specific, bureaucratic, and strangely polite. It prefers “comprehend”, “boast”, “swift”, and “meticulous”. It favors “underscore”, “bolster”, “inquiry”, and “pinpoint”, all used without meaning, to smooth over the rough edges of thought in the tone of a machine-predicted hallucinatory consensus that does not exist.

This usage might simply be a matter of writing produced by an LLM with professors, podcasters, and YouTubers reciting from a script, which is certainly part of it. The study found that academic talks, which are often scripted, showed the most dramatic shifts. However, spontaneous dialogue like podcasts showed the same pattern with one proviso. The changes are not consistent across contexts. They thrive in the jargon-rich environments of technology, business, and academia. Maybe in these domains, the urge to sound authoritative and correct makes the speaker vulnerable to machine-inferred language, in a voice that sounds like a mid-level administrator who has read too many manuals. Maybe this is just how most people in the academic and professional worlds wish to sound. Interestingly, the domains of religion, spirituality, and sports remain largely resistant. Perhaps there is something in the raw tribalism of sports or the esoteric wandering of spirituality that the algorithm cannot yet comprehend or meticulously replicate.

The immigrant researchers at Max Planck note that ChatGPT exhibits a “persistent preference for normative and socially desirable communication patterns” and warn of “erosion of linguistic and cultural diversity.” Chat is polite, avoids conflict, and defaults to a “structured and formal etiquette.” When we adopt its language, we adopt this same distinct ethical posture and tone of OpenAI’s policies. In letting AI dictate our discourse, we let a reinforcement learning process, driven by underpaid workers in Kenya and elite corporate politics turn us too into safe space doormats.

The authors suggest that words like “delve” could eventually become “stereotypically associated with lower skill or intellectual authority,” signs of a mind that has outsourced its thinking. One would hope that the literate among us, like the editors at The California Review, can continue to spot the obvious tone, style, vocabulary, and phrasing of these offenses. In written text, things like uniform paragraph lengths, negating nonsequiturs, inapposite switching between participles and verb voices, and enough weak arguments to make an LSAT-studying student gouge his own eyes out are always a dead giveaway (see Cal Review style guides below). We may eventually reach a point at which speaking with the voice of a probabilistic text generator is an admission of stupidity, or at least a lack of literacy or education. Mutatis mutandis, for the literate among us who know better, it also becomes an indicator of a true educated class, an immune control group for our social experiment.

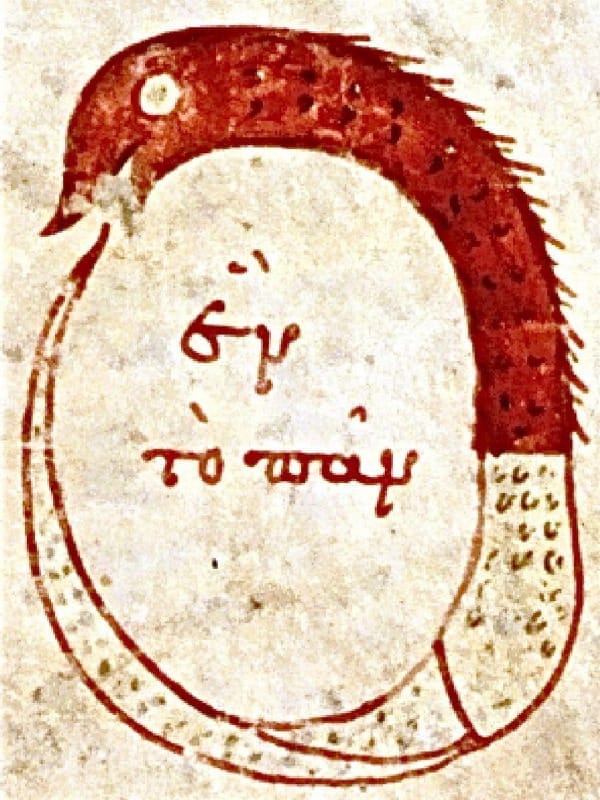

For now, the precipitous line on the graph goes up and to the right. The “delving” persists. The machine was made in our image and, in an ouroboros of inanity, we are remaking ourselves in its. The research paper suggests the possibility of eventual model collapse, where LLM inferences, feeding back on their own output data, become increasingly incoherent to even their illiterate “low... intellectual authority” users. But, based on the study, the collapse of the humans, the consultants, VC’s, and academics, is more imminent.

The California Review recommends the following:

The Elements of Style, Strunk and White, 1919

Politics and the English Language, George Orwell, 1946

Authority and American Usage, David Foster Wallace, 1999

Guidelines on Writing a Philosophy Paper, Jim Pryor, 2006

A Sense of Style, Steven Pinker, 2014